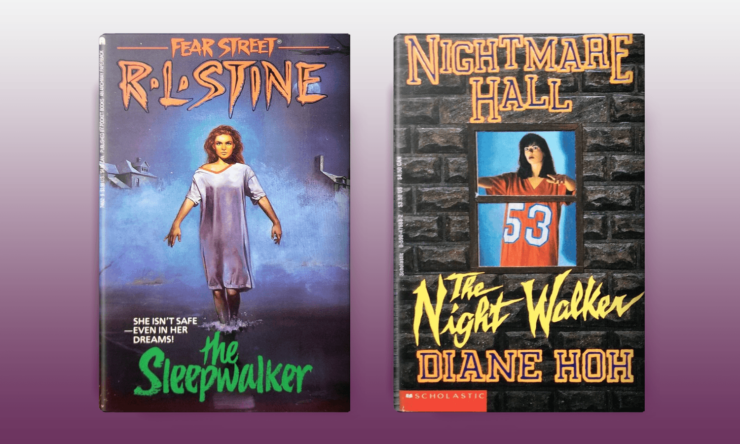

All kinds of dangers lurk in the shadowy corners after darkness falls, which are often compounded by the terror of one’s own nightmares. But in R.L. Stine’s The Sleepwalker (1990) and Diane Hoh’s The Night Walker (1994), characters encounter the worst of both worlds when they find themselves walking in their sleep, unable to remember where they have been or what they have done, as inexplicable threats and mysterious attacks pile up around them. In addition to the fear they share with their friends as they try to figure out what’s really going on, both of these characters find themselves wondering how well they know themselves and what they’re capable of.

There’s a lot of potential here for exploring the mysteries of the unconscious mind and the hidden depths of the human psyche, and while these books are ill-equipped to actually solve any of these riddles, the lengths they go to in order to figure things out reflect their characters’ deep-seated fear of both themselves and others.

In Stine’s Fear Street novel The Sleepwalker, Mayra Barnes gets a summer job working for a mysterious old woman named Mrs. Cottler. Mrs. Cottler has a black cat and a drawer full of black candles, and when she gets in an argument with her next door neighbor (the peaches from her tree are falling in his yard and he’s mad as hell), she picks up a handkerchief he dropped on her porch and the next day, he has a bad accident. Mayra quickly jumps to the conclusion that Mrs. Cottler is a witch, and when Mayra starts sleepwalking shortly after starting her summer job, she’s certain that Mrs. Cottler has put a spell on her. Mayra keeps waking up in strange places in the middle of the night, sometimes having walked for a couple of miles. In one particularly memorable sleepwalking episode, Mayra wakes up to find that she has walked into the lake near Fear Street, in serious danger of drowning before she is rescued by a passing fisherman. As if that weren’t bad enough, her ex-boyfriend Link is persistently pursuing her in an attempt to get back together and her new boyfriend Walker is spending time with Suki Thomas, who is “just about the trashiest girl in school” (44) (and for my money, hands down the most interesting character in the whole Fear Street series). Her friend Stephanie is Link’s sister and is mad at Mayra for breaking up with him, Mayra’s mom doesn’t take her sleepwalking problem all that seriously at first, and some weird guy she’s never seen before suddenly starts yelling at Mayra and chasing her down the street when he sees her. All in all, it’s not the best summer of Mayra’s life.

Buy the Book

A House With Good Bones

Mayra is determined to get to the bottom of things and has a couple of witch-y leads: first, when she’s housesitting for Mrs. Cottler and snooping through her things, she finds a whole library full of books on witchcraft and the occult, plus a birthday card from Link and Stephanie, who it turns out are Mrs. Cottler’s nephew and niece. When Mayra runs over to Stephanie’s to confront her about setting her up, she finds Stephanie doing a spell of her own, which complicates things. Is it Mrs. Cottler casting the sleepwalking spell on Mayra, is it Stephanie, or is it both of them? It turns out it’s actually neither and while Stephanie is genuinely interested in the occult, her aunt is a pretty famous academic whose research focuses on magic and witchcraft. While neither of them cast a spell on Mayra, the familiar fear of women’s power—whether magical or intellectual—lead both Mayra and the reader to view them as potentially dangerous, worthy of suspicion.

Even though Mayra and Stephanie have been good friends for several years, Mayra immediately becomes frightened of Stephanie when she thinks Stephanie may have powers that Mayra cannot control or resist; Mayra also is really quick to jump to the conclusion that Stephanie would even want to hurt her in the first place, which provides a demoralizing peek behind the curtain of the strength and stability of this particular female friendship. Boy trouble and the threat of female power are all it takes to knock it down.

There are also a lot of roads not taken in considering Mrs. Cottler’s potential power—when Link tells Mayra that his aunt is a respected scholar, it’s intended to put Mayra’s mind at ease, through the validation of the formal education system (which often isn’t equitable for women, whether as students or professionals). She’s an “expert,” which presumably offers the reassurance of more confinement and control than if she was a “witch”—she’s official and as such, has to play by the rules of the academic system. Given this legendary expertise, it’s also pretty devastating that no one in her small town (or at least no one we see) knows or cares about these accomplishments. She’s written off as a kook or a crackpot, and she isn’t even given the well-earned respect of being referred to as Dr. Cottler or Professor Cottler, but rather as Mrs. Cottler, which paints her into a corner of domestic and marital identity, rather than acknowledging her intellectual brilliance and the respect she’s afforded in those professional circles. And while Dr. Cottler’s professional position works to erase the possibility of her having magic powers, why can’t it be both? Why can’t she be both a witch and an expert, a practitioner and an academic? To be fair, I think Stine’s conclusion at least raises this possibility, but it’s a reality that the majority of the characters feel the need to reject and silence, contain and dismiss. A smart woman is easier to neutralize and live with than a magically powerful one, apparently, particularly if you’ve already denied her the recognition of her academic accomplishments and deserved title.

The psychiatrist Mayra sees, Dr. Sterne, offers a theory of his own in their initial consultation, telling Mayra that her sleepwalking could be “caused by repressed trauma … You’re trying to deal with it when you’re asleep because you find it too upsetting to deal with when you’re awake” (122). However, it’s not until Mayra falls in a lake—this time while she’s awake and trying to get away from Link, who really won’t take no for an answer, though that’s a totally separate trauma and one that goes largely unaddressed—that she realizes what it is she has forgotten and why. Throughout the book, Mayra’s boyfriend Walker has generally been presented as a pretty bland nice guy who bores everyone to tears with his magic tricks, but it turns out that he’s actually kind of a bad boy and when he and Mayra were on a date at the mall at the start of the summer, he stole a car, took it on a joyride, and then ended up getting in an accident, where the other car fell over the side of a cliff and into the lake, killing one of the passengers. While Mayra wanted to stay and help, Walker forced her back into the car and fled the scene, then hypnotized her to forget the whole thing, which opens another mysterious door to the subconscious (though this one is also problematically oversimplified).

Walker’s only staying with Mayra to make sure her memory’s not going to come back, the angry stranger chasing Mayra is the guy who survived the car crash while his brother died, and the only way for Mayra to get to the truth is to pretend to let Walker hypnotize her again so she can lure him into confessing when he thinks she won’t remember. Things get really real when Mayra learns the truth and confronts Walker, who literally tries to kill her and nearly succeeds before Mayra is (possibly magically) saved by Mrs. Cottler’s black cat, Hazel, who manages to escape the house to save Mayra at the lake and is somehow also still waiting at the house, locked safely inside, when Mayra gets there. While heroic Hazel offers a potentially happily ever after, Mayra’s love life arguably takes a more problematic turn when she gets back together with Link, forgiving him when he tells her that “The only reason I was such a creep was that I cared about you so much” (161). Link has spent the entire novel following her, harassing her, ignoring her when she tells him she doesn’t want to see him or talk to him, and even physically restraining her when she tries to run away from him, but he at least isn’t covering up a murder, controlling her through hypnosis, or trying to kill her, so he’s the “good guy.” Mayra now likes Mrs. Cottler—though only once she has self-deprecatingly identified herself as “a tiresome old lady” (163) and eschewed any power she has—and now that Mayra’s back with Link, she’ll probably be friends with Stephanie again, though the reconciliation of this female friendship isn’t important enough to warrant a mention in the novel’s closing pages.

In The Night Walker (Nightmare Hall #9), the cause of Quinn Hadley’s sleepwalking is less dramatic: periodically throughout her life, when she’s been under a great deal of stress, she has experienced bouts of sleepwalking, and her transition to college life at Salem University seems to have prompted another one. Quinn’s sleepwalking never lasts for long and she’s never done anything dangerous when she sleepwalks, but this time around, Quinn’s episodes coincide with a series of attacks on the Salem University campus–and Quinn finds herself wondering if she might be the perpetrator. Quinn has recently been dumped and all the attacks around campus seem to target happy couples, including a stink bomb that detonates during a spring formal, a whole bunch of red paint poured from the upper story of a building onto two lovers below, and a couple who find themselves trapped in their car when someone attacks the vehicle with a hammer.

Quinn suspects herself but she also suspects her roommate Tobie, who is hiding a traumatic secret of her own: she saw her boyfriend Peter killed in a mugging gone wrong. Tobie testified against his attacker, Gunther Brach, who is now in prison, but Tobie is still heartbroken and unable to move on from this tragic loss, regardless of how many eligible campus bachelors her friends throw at her. While Quinn is overwhelmed with sympathy for Tobie, she also can’t help but wonder if this is the kind of thing that might prompt someone to attack people in love, an expression of anger and resentment for the love Tobie can’t imagine ever finding again.

Much like the surprising secret identity of Walker in The Sleepwalker (whose guilt, come to think of it, is right there in the title—the Sleep Walker!), in The Night Walker, the culprit is similarly someone who is pretending to be someone they’re not: in this case, Quinn and Tobie’s friend Ivy, whose real name is Salina Ivy Gunn and whose real identity is Gunther Brach’s vengeful girlfriend. Salina feels that Gunther has been treated unfairly—he’s not bad, just misunderstood, it’s not his fault that Peter fell and hit his head, and if Peter had just given Gunther the money in the first place, they could have avoided all this unpleasantness—and she wants to make Tobie pay. Salina’s brilliant plan is to commit a series of attacks on campus and frame Tobie for them, and when Tobie gets sent to prison, “she’ll find out firsthand how Gunther has suffered” (182). An integral part of Salina’s plan was for Quinn to find the “evidence” she planted in Quinn and Tobie’s room and go to the police with it, but when Quinn finds the stink bombed and paint splattered clothes and the hammer, she suspects herself and hides the evidence instead of going to police, stalling Salina’s revenge plot. When Salina learns about Quinn’s sleepwalking, she decides to twist this to her own advantage as well, planning to make it look like Tobie is trying to frame Quinn, which she hopes will make Tobie look even more devious and guilty, because “If she was sane enough and rational enough to be so meticulous in her planning, how could she possibly plead insanity?” (177). The only person who knows what really happened and could tell a different story is Quinn, which is why Salina has to kill her.

Quinn and Tobie live in the Deveraux dorm, but the action inevitably ends up taking the horror to the series’ eponymous Nightmare Hall, the students’ nickname for Nightingale Hall because of all the weird and spooky things that happen there. Salina chases Quinn through the woods and corners her inside an old barn on the Nightingale Hall property. Quinn goes up the ladder to hide in a hayloft where Salina corners her (seriously, that’s a Slasher 101 no-no). Quinn pushes the ladder away from the hayloft when Salina begins to climb up and Salina plunges to her death, along with an oil lantern that sets the whole barn ablaze, with Quinn trapped in the hayloft because she’s now lost the only ladder. Quinn finds a small door for hoisting hay bales and after a daring rope and pulley maneuver, coupled with the awakened residents of Nightmare Hall waiting with a blanket to catch her below, Quinn escapes the burning barn, tells her story to the police, and is finally able to get a good night’s sleep (though it seems like the stress of a near-death ordeal would be a perfect storm for further sleepwalking, if stress is Quinn’s particular trigger).

In The Sleepwalker and The Night Walker, there is a combined suspicion of both one’s self and others. Both Mayra and Quinn’s first instinct is to figure that there’s something “wrong” with them, something that needs to be controlled or fixed that remains mysterious or outside of their control. The sleepwalking incidents themselves also suggest a similar internal cause: a subconscious impulse or repressed desire that takes over when these girls’ minds and bodies are unaware. And while there’s definitely some interesting stuff to dig into there—Mayra’s subconscious working to right a wrong she didn’t consciously remember and the largely unidentified stressors that prompt Quinn’s nighttime strolls—in each case, there is even more danger coming from outside of these young women than from within their own minds. Walker’s hypnosis is self-serving and exploitative; he keeps Mayra close for surveillance and control, and when those goals prove unsustainable, he’s ready to kill her. Quinn isn’t Salina’s intended target and is initially no more than a complication and an obstacle as Salina works to frame Tobie, but when Salina realizes that Quinn has been sleepwalking, she immediately manipulates the situation to further her own devious plans. There is an intentional dissonance between Mayra and Quinn’s internal experiences of their sleepwalking episodes—which are disorienting, terrifying, and make them second-guess everything they think they know about themselves—and the external machinations of people who want to capitalize on their fear and confusion to get what they want.

Whether it comes from their own subconscious minds or from people who want to hurt them, for Mayra and Quinn, the danger is inescapable. Asleep or awake, alone or with others, nowhere is safe. Sweet dreams.

Alissa Burger is an associate professor at Culver-Stockton College in Canton, Missouri. She writes about horror, queer representation in literature and popular culture, graphic novels, and Stephen King. She loves yoga, cats, and cheese.